I love writing software. But using tools like Scrivener or Microsoft Word to build my worlds, I ran into difficulty with critical documents becoming corrupted and proprietary formats that became obsolete as the software entered its next phase of development.

As the author of over 130 published books, it might seem counterintuitive that I would choose to write in an application built on the digital equivalent of a blank sheet of paper: plain text files in Obsidian.

Here are five powerful reasons why I prefer simplicity and power over bells and whistles.

1. My Biggest Fear is File Corruption. Plain Text is My Armor.

My work is safer in small, independent files.

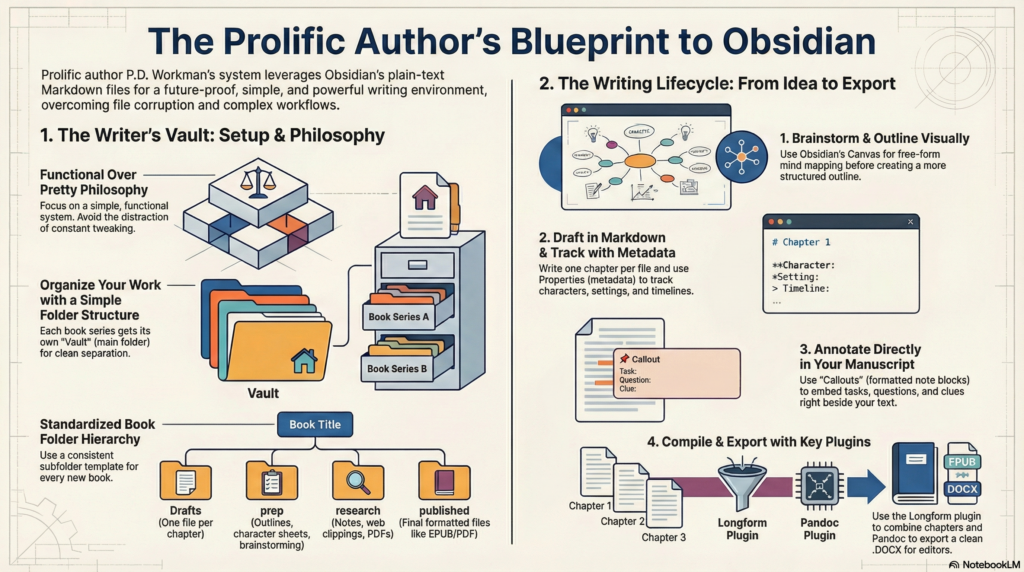

The core of my writing system hinges on a fundamental change in how I store my books. Instead of typing my story into one massive file that contains my entire novel, each chapter or scene is saved as its own separate lightweight plain text (.md) file. This shift has profound implications for the stability of my work.

One problem I experienced when using Scrivener or Word to write books was that big files are prone to corruption, and can take a lot of memory or processing power. While I know a lot of authors who have never experienced this large-file corruption, I write a lot more than most of them, so it naturally follows that I will experience problems like corruption more often.

This problem is reduced or eliminated by dealing with small text files rather than a huge word-processor file. I still end up producing a .DOCX file for my editor and .VELLUM and .PDF files as part of the publication process, but the chances of corruption are greatly reduced if you are not making amendments to the files. They are essentially finalized and frozen in place.

But for documents that are changing daily, plain text will never become obsolete.

2. I Don’t Need a Complicated System (In Fact, It’s Better If I Don’t).

The goal is to finish books, not build the perfect dashboard.

Obsidian can be endlessly customized into an intricate personal knowledge management system, but I do not spend a lot of time playing with the appearance of my vaults or building complicated systems. I build what is needed, and then use it. It is functional rather than pretty. I have refined my use of Obsidian over the years, eliminating friction points and folding in new features as they are added—though I have a rule that I don’t experiment with a new feature while I am drafting. I have to wait until the end of the month to “play” with anything new.

In a world saturated with productivity methodologies like Zettelkasten or PARA, I’ve opted for a straightforward hierarchical folder structure—a universal organizing principle that persists across all platforms at a system level. This choice is essentially about ensuring my entire body of work remains portable, readable, and organized without being confined to any app’s logic.

By keeping things simple in my setup, I’m able to leverage Obsidian’s power and flexibility without getting lost in unnecessary details—it helps me write smarter, stay organized—and finish more books.

3. It’s Not Just a Note-Taker; It’s a Complete Writing Studio.

With two key plugins, this simple text app becomes an end-to-end professional workflow.

A common obstacle with plain text chapters is transitioning from multiple individual files into one complete formatted manuscript. However, I’ve transformed Obsidian into an efficient writing studio by implementing workflows that cover everything from brainstorming ideas to final export—all thanks to two essential plugins:

- Longform: This plugin compiles all my chapters into one cohesive document by intelligently gathering individual scene files.

- Pandoc: This powerful tool converts my compiled document into .DOCX format—the standard used in publishing.

The .DOCX file generated by Pandoc isn’t necessarily the final product; it serves as the clean manuscript sent off for editing. After making edits based on feedback from editors or beta readers, that finalized Word document usually gets imported into Vellum—a dedicated formatting program—to produce polished print and ebook versions for publication.

4. Embedding a Database Directly In My Manuscript.

Tracking characters, timelines, and settings becomes effortless with precision.

At the top of each chapter file in Obsidian, I utilize Obsidian “Properties” (also known as a YAML header) to keep track of essential metadata for every scene—essentially turning each file into its own mini-database entry. To enhance clarity even further when tracking data types such as:

Character: Which characters appear (e.g.,;Manny).Setting: The location (e.g.,~bridge).Day: The timeline day for continuity.Draft: The current draft version number for each scene.

The power of these properties emerge when using plugins like Dataview or Bases plugin; this metadata allows me to create dynamic summaries across scenes instantly! Imagine generating tables showing every instance where specific characters appear—all without losing valuable context since this data resides within plain text itself!

You can see I preface Character names with ; and Setting names with ~. This allows me to search/filter them quickly if I am viewing them from the MacOS File Finder or another program rather than within Obsidian. Why would I not just search Malachi instead of ;Malachi? Because I don’t want to bring up every scene in which Malachi is mentioned by another character, only the scenes in which he is present.

5. Leave Notes for Myself Everywhere… and Make Them Disappear on Command.

A sophisticated annotation system eliminates clutter during export while enhancing productivity during writing sessions!

As writers often do—I leave notes for myself throughout drafts—but managing them can become chaotic quickly! Thankfully—I’ve developed an elegant method for embedding annotations directly into manuscript texts using:

- Checkboxes (– [ ]) indicating active tasks like “research this poison” or “foreshadow this clue earlier.”

- Callouts (> [!Clue]**) mark significant clues distinctly—ideal when crafting mysteries!

- The 999 marker, which serves as searchable tags denoting items needing revisiting—selected because it was easy enough typographically while allowing search previews displaying relevant context!

Most impactful? At compile time using custom steps in the Longform plugin—I automatically strip out front matter, comments, checkboxes, callouts, etc.—resulting in perfectly clean professional documents free from stray notes before sharing them with editors!

My Writing Tool Should Serve Me—not Vice Versa

A good writing tool must eliminate friction while keeping focus squarely on creation! Choosing simplicity and clarity over flashy features, I’ve established systems designed for longevity.

As you reflect upon your own process consider asking yourself: What single point causes friction within your current workflow? Could adopting a simpler, more direct solution be beneficial?

- Why write a novel in plain text instead of Word or Scrivener?

Plain text files are lightweight, portable, and less likely to become corrupted and will not become unusable due to proprietary format changes. - Can Obsidian handle full-length novel projects?

Yes. With a chapter/scene file workflow and plugins like Longform, Obsidian can manage drafting through manuscript assembly. - How do you export from Obsidian to DOCX?

Use Longform to compile scenes, then Pandoc to convert the compiled manuscript into DOCX for editors. - Is plain text too minimal for complex fiction projects?

Not at all! You can use basic markdown formatting, and with metadata (YAML/Properties) for characters, settings, timeline, and draft tracking, tasks, linking, and callouts for comments, it is a very robust solution. - How do you keep notes in drafts without exporting them?

Use checkboxes, callouts, and markers during drafting, then use Longform steps to strip them during compile/export. - Can this workflow work for beginners?

Yes. Start with a simple folder structure and basic markdown, then add plugins only when needed.